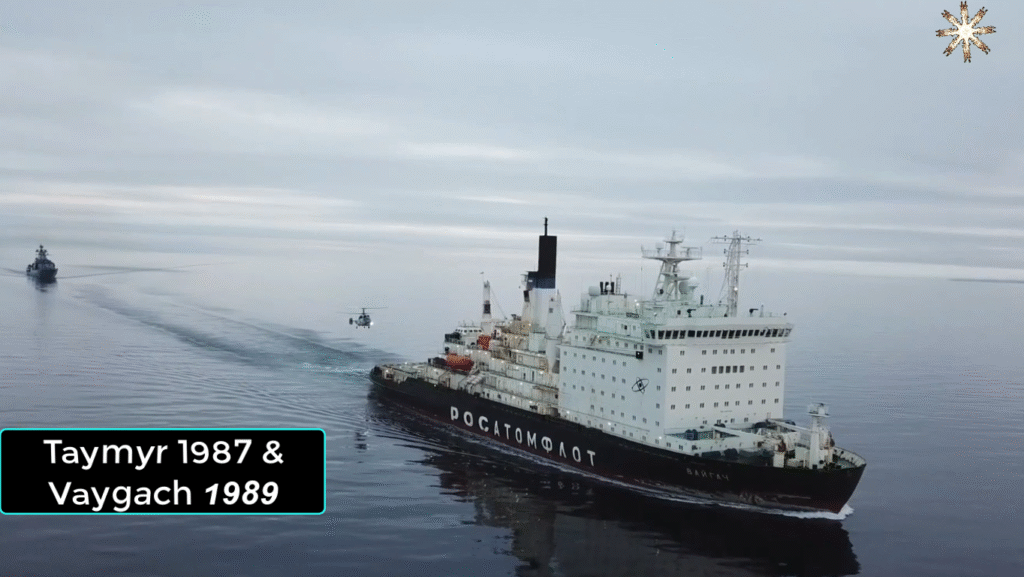

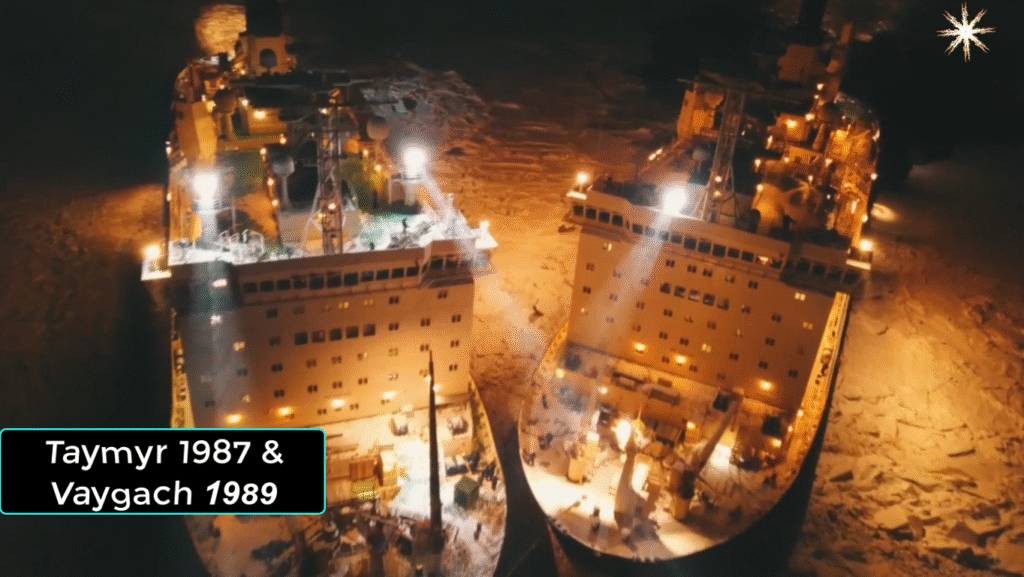

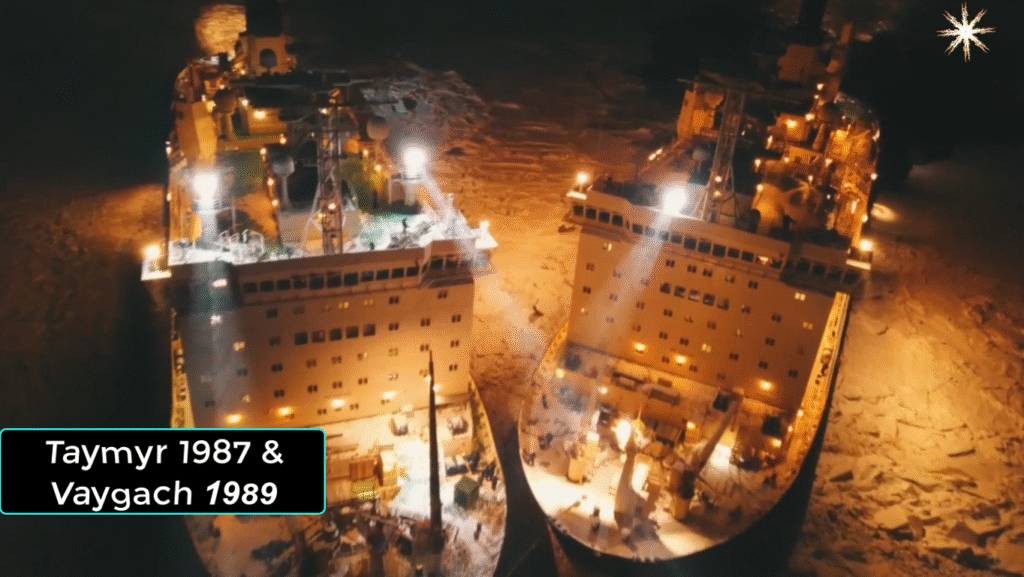

At the far margins of the map, where Siberia dissolves into ice and silence, two ships have spent their lives rewriting the meaning of endurance. Taymyr and Vaygach—names borrowed from Arctic geography—are not vessels that command instant recognition. They do not loom like floating cities, nor do they appear in dramatic launch photographs meant to signal national power. Yet for decades, they have quietly shaped the daily reality of the Russian Arctic, performing work so essential that its absence would be unthinkable.

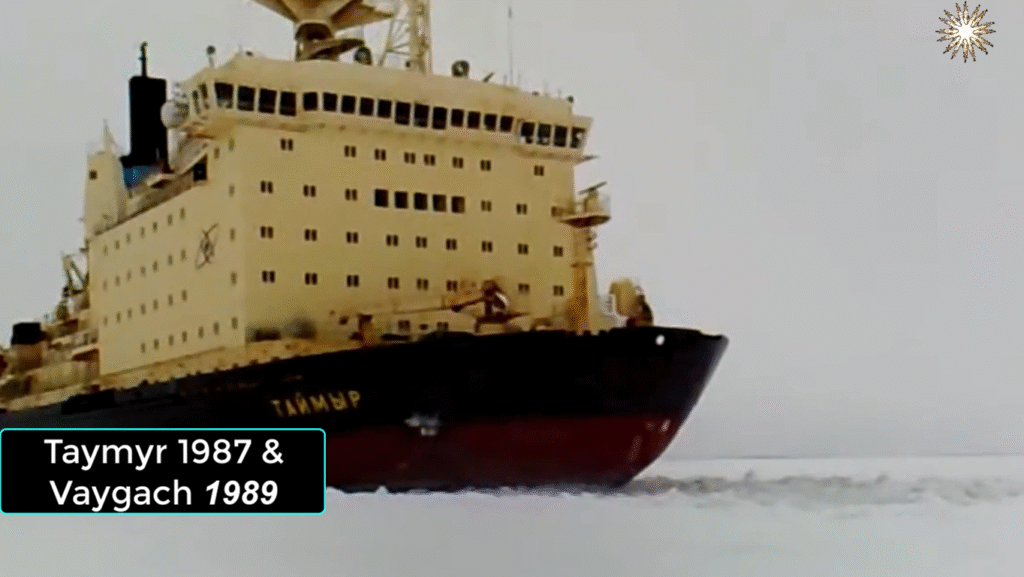

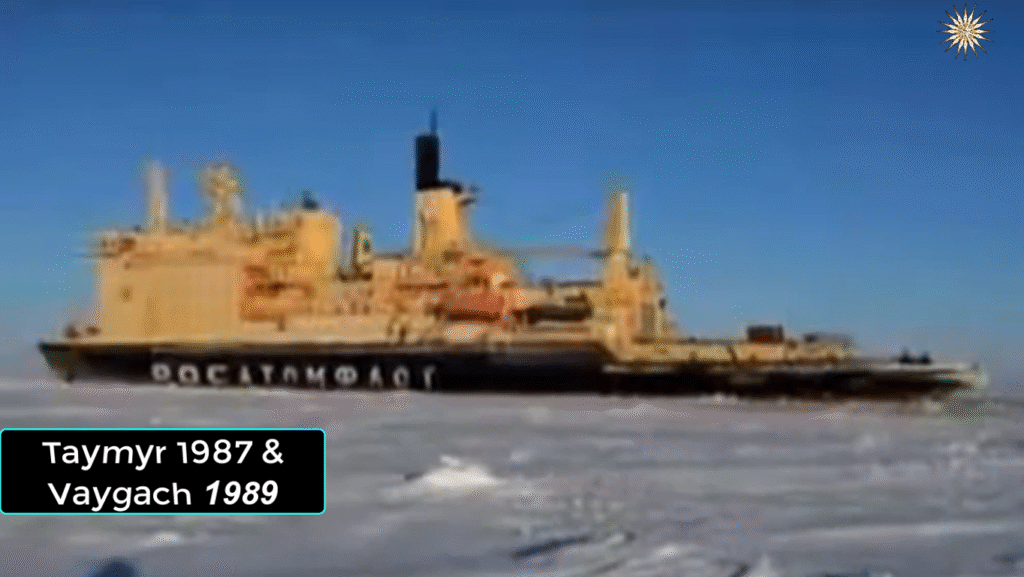

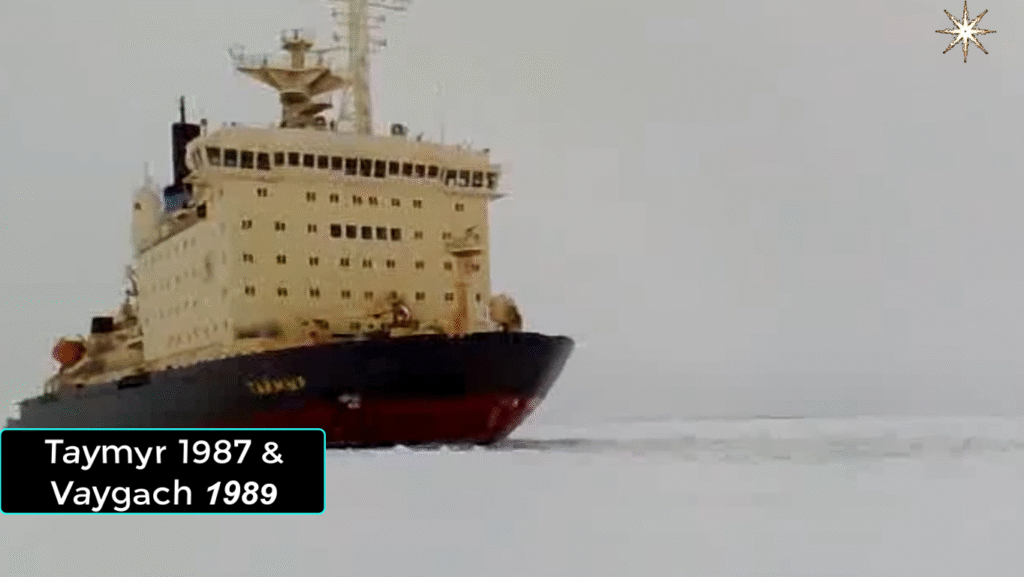

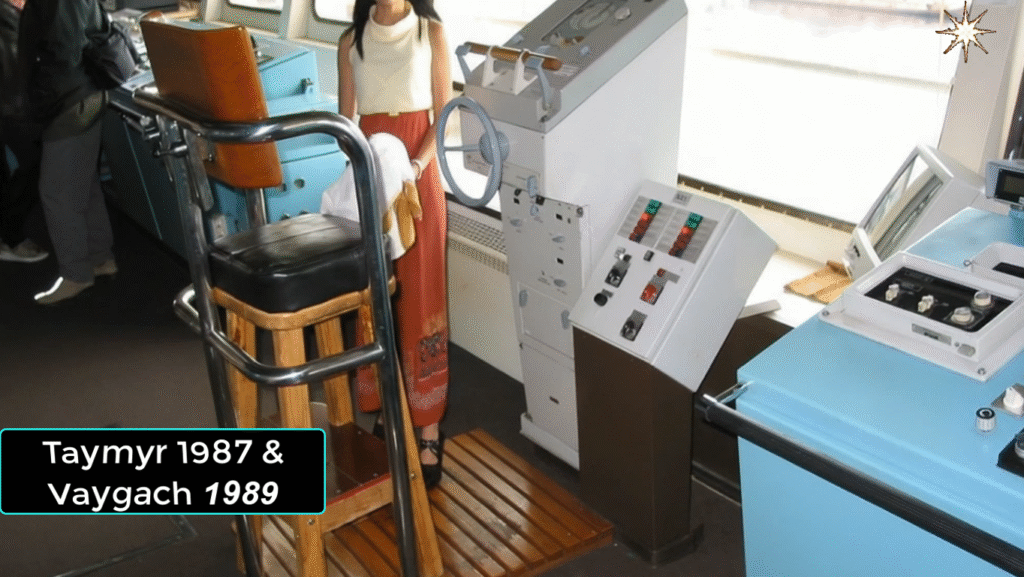

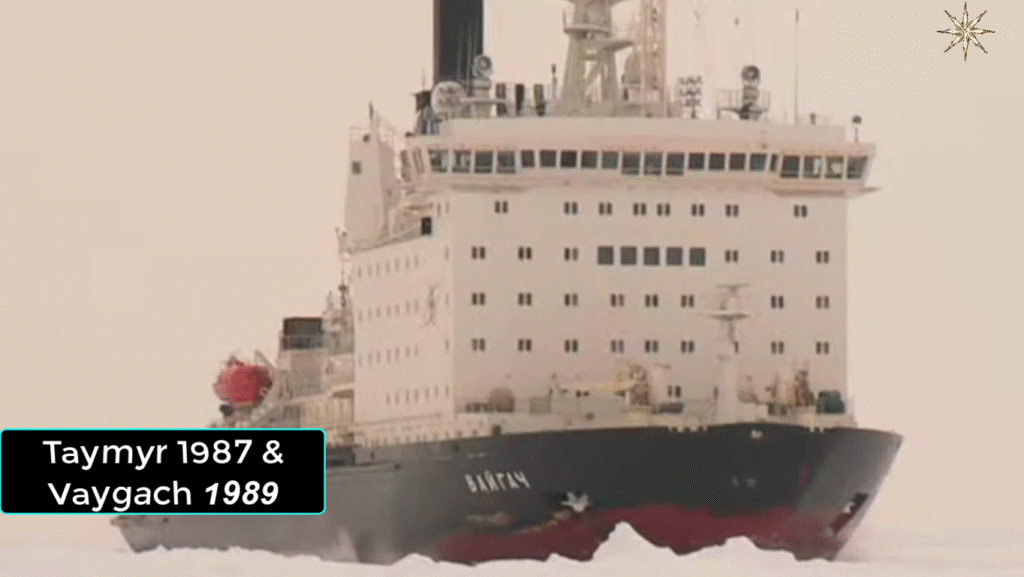

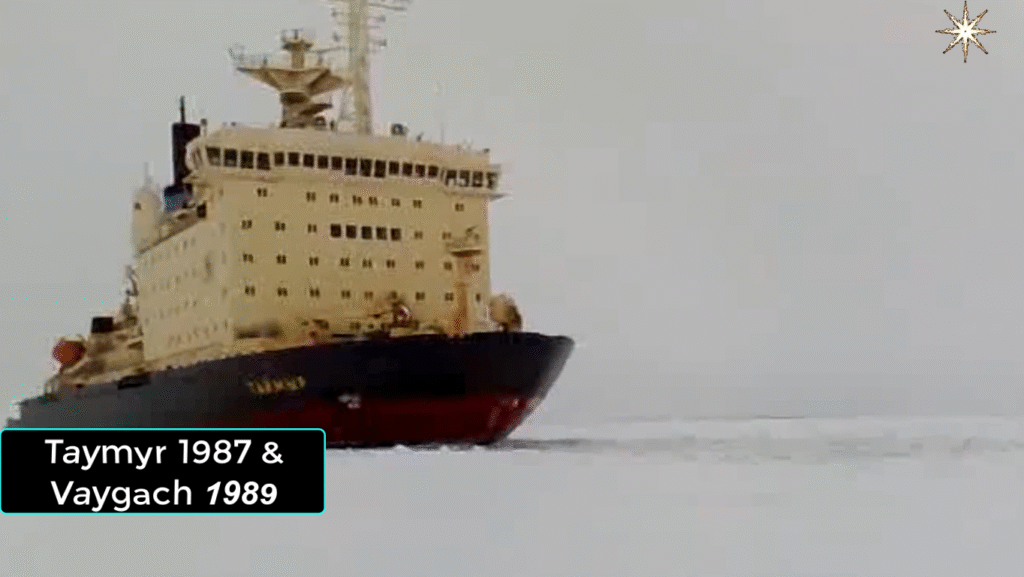

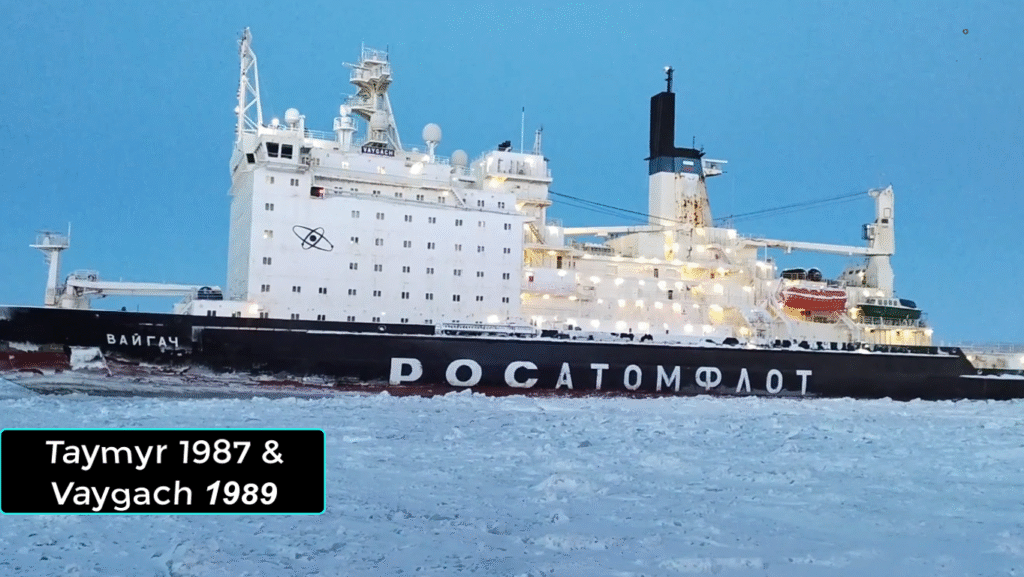

Conceived during the final years of the Soviet Union, Taymyr (commissioned in 1987) and Vaygach (1989) were designed for a problem few ships could solve. The great Siberian rivers—the Yenisei above all—are lifelines stretching thousands of kilometers inland, but where they meet the Arctic Ocean, nature conspires against navigation. Ice pressure, shallow waters, shifting sandbanks, and extreme cold form a barrier that traditional icebreakers, with their deep drafts, cannot easily cross. The solution was radical in its restraint: compact nuclear icebreakers with shallow drafts, powerful enough to break ice, yet agile enough to operate where sea and river blur into one.

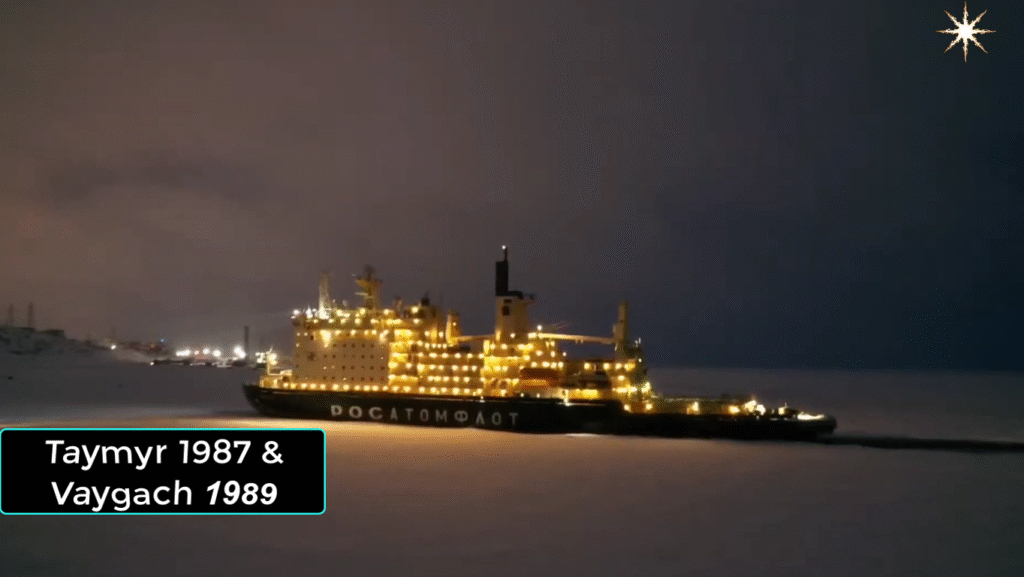

Built in Finland but powered by Soviet nuclear technology, the two ships embodied a rare fusion of international craftsmanship and late–Cold War ambition. Their reactors granted them extraordinary endurance, freeing them from the constant logistical burden of refueling. This autonomy mattered less for spectacle than for reliability. In the Arctic, schedules are fragile things, and a single missed convoy can isolate entire regions for months. Taymyr and Vaygach were built to ensure that did not happen.

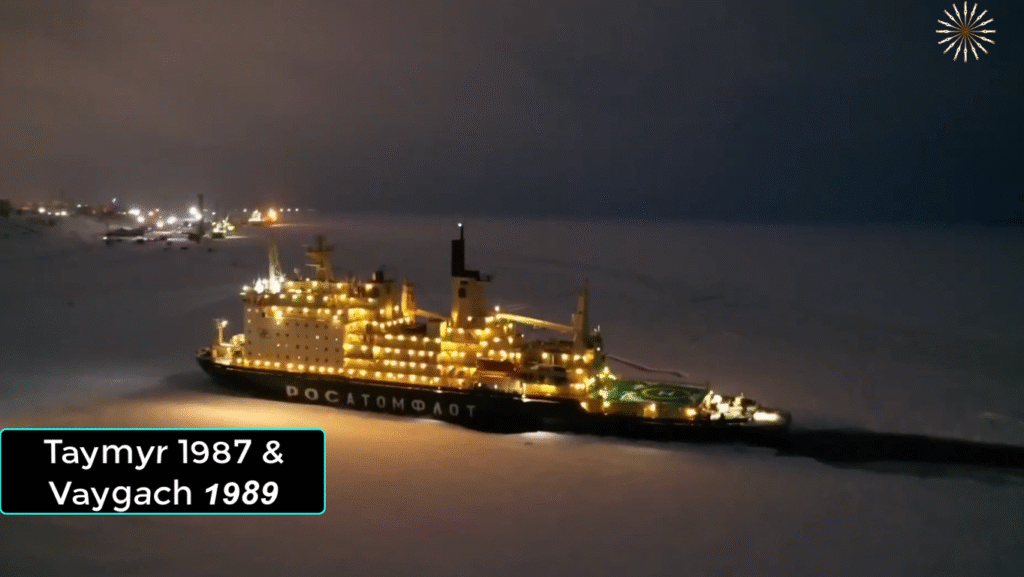

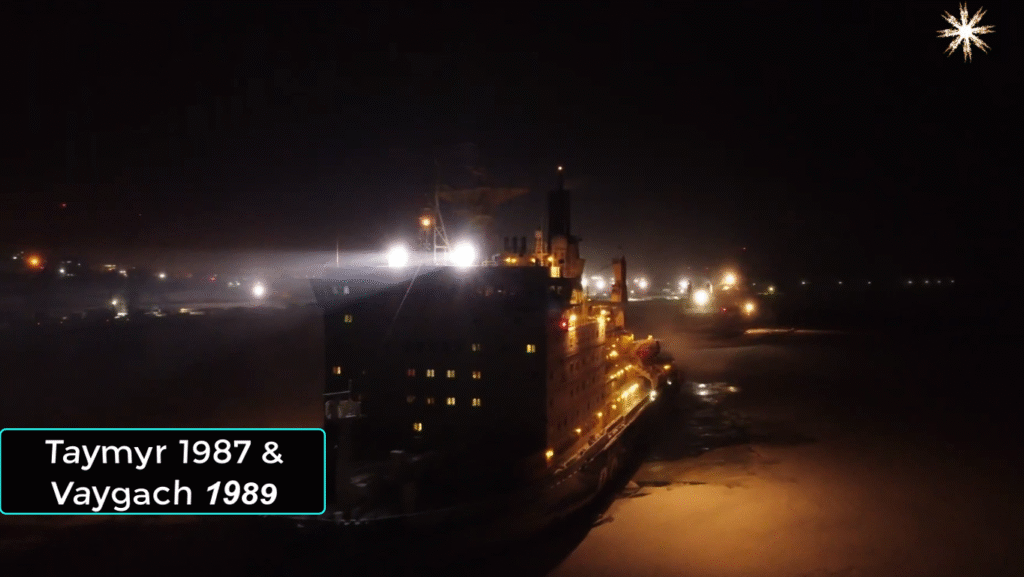

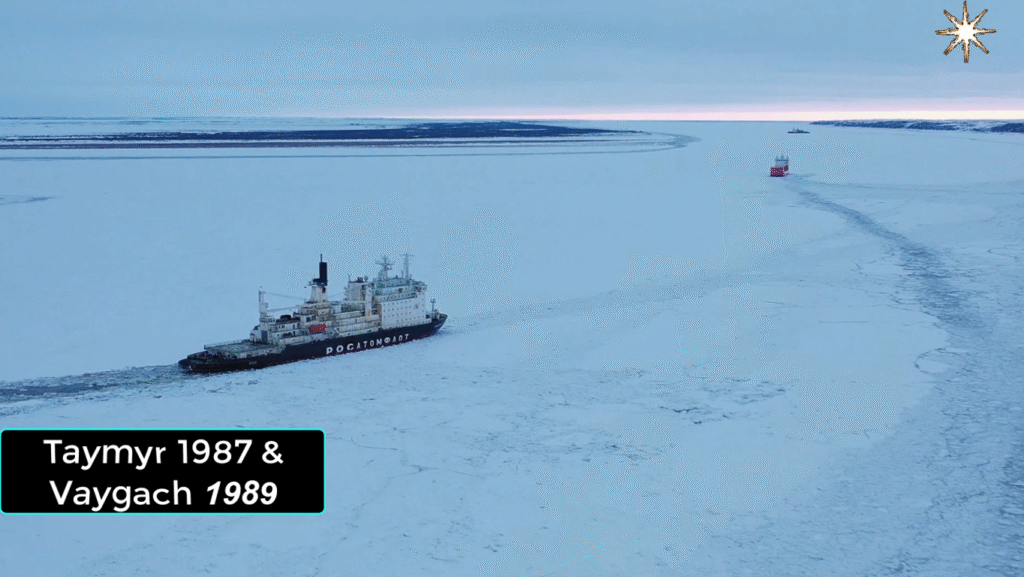

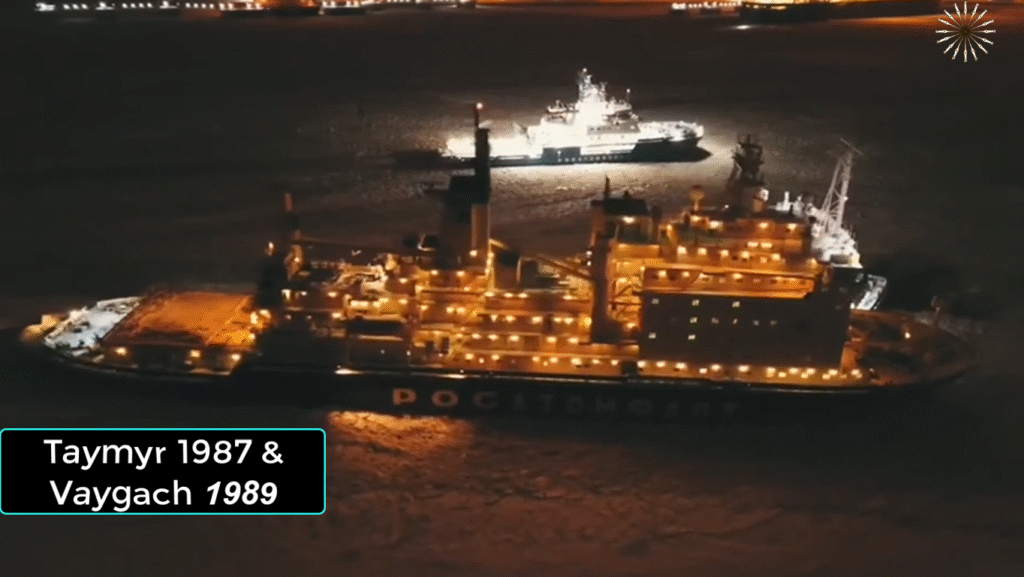

Their working lives unfolded far from ceremony. Season after season, they escorted cargo ships carrying fuel, food, machinery, and raw materials—cargoes that sustained northern towns and industrial outposts. They broke channels through ice that re-formed with stubborn regularity, returning again and again to the same routes, learning their moods and dangers. Unlike larger nuclear icebreakers that opened the Northern Sea Route across vast expanses of ocean, these ships specialized in the in-between places: estuaries, river mouths, and coastal shallows where precision mattered more than brute force.

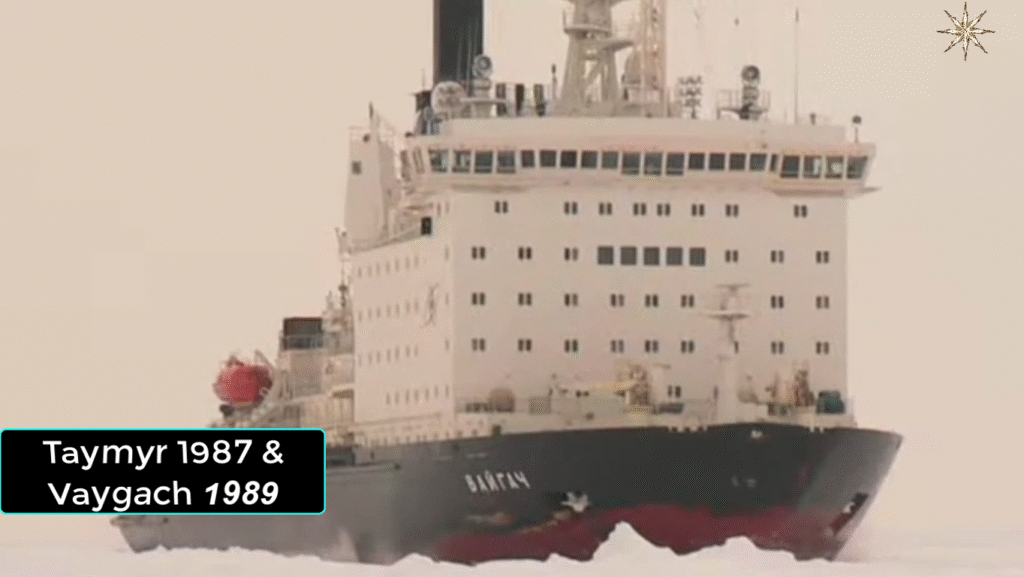

When the Soviet Union collapsed, many symbols of its technological confidence fell into neglect or obsolescence. Taymyr and Vaygach did not. They passed quietly into a new political era, continuing their work with little alteration to their mission. Flags changed, institutions were restructured, but the ice remained—and so did the need for ships that could tame it. Their continued operation became a reminder that some forms of engineering transcend ideology, anchored instead in geography and necessity.

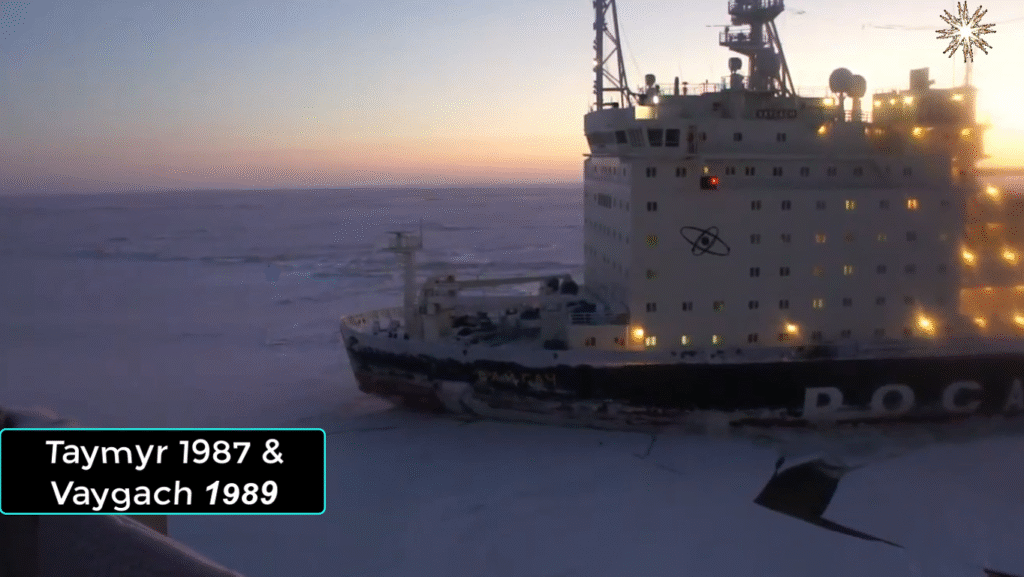

In recent years, as climate change redraws the Arctic and global attention turns northward, the relevance of these two vessels has only grown. Thinner ice has not eliminated danger; it has made conditions less predictable. Shallow-draft nuclear icebreakers remain uniquely suited to navigating this uncertain environment, where flexibility is as valuable as power. While newer, more advanced ships now dominate headlines, Taymyr and Vaygach persist as living links between eras—proof that thoughtful design can outlast the moment that created it.

Their story resists easy symbolism. They are not monuments, nor are they relics. Instead, they represent a quieter tradition of maritime achievement: ships built with humility, tailored precisely to their task, and judged not by fame but by consistency. In the Arctic, where nature rarely yields completely, success is measured in passages kept open, communities supplied, and winters endured without catastrophe.

Seen this way, Taymyr and Vaygach are less machines than companions to the landscape they inhabit. They move slowly, deliberately, pushing against ice that has shaped human limits for centuries. And as long as rivers continue to meet the frozen sea, their legacy will remain etched not in museums, but in the narrow, hard-won channels they carve through the ice—again and again, year after year.